A. Embree : 1968 Columbia Student Revolt Remembered in New York

Columbia 1968: The View From Texas

By Alice Embree / The Rag Blog / May 3, 2008

[Alice Embree is an Austin activist, writer and Ragblogger. She played a major role in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in the sixties and seventies, both in Austin and New York, and wrote for underground papers Rat and The Rag.]

In April 1968, Columbia University erupted in protest. Students occupied five buildings. I was there. I wasn’t a Columbia student, but I was there. I worked with the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) and caught a briefcase full of documents tossed from the second floor Low Library office of Grayson Kirk’s office that were re-printed in RAT newspaper and used to document the NACLA pamphlet, Who Rules Columbia?

I was at Columbia again April 24-27 for events commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the student uprising. The 1968 occupations were motivated by two major demands - to stop a Morningside Heights gym expansion and sever ties with the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA). Antiwar passion and black liberation struggle were a potent mix. When the police cleared the buildings forty years ago, they arrested 700 students and left 150 injured. It was a pivotal event for students in a year marked by historic events.

1968 began with the Tet Offensive demonstrating the strength of the Vietnamese national liberation resistance. On April 4, 1968, Martlin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis and cities went up in flames. The Columbia strike occurred just weeks before a general strike in Paris. On June 5th Robert Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles. In August, tanks rolled into Prague and the National Guard was called up in Chicago where antiwar protestors massed outside the Democratic Convention and were attacked by Chicago police. A student uprising in Mexico City was brutally suppressed in the October 1968.

The Columbia gathering drew several hundred alumni of the protests with their nametags identifying the buildings they occupied: “Hamilton Hall, ’68,” “Mathematics, ’68,” etc. People found old friends and comrades, often needing to be prompted to reconcile gray hair or balding heads with the faces of youth.

On Thursday, the first night, there was a reception followed by a panel on Columbia and the World. Tom Hayden (Mathematics) recalled that year as did Black student activist William Sales (Hamilton Hall). Mark Kurlansky, author of 1968: The Year That Rocked the World, and Victoria de Grasso spoke of the world events that year.

Friday morning, Michael Klare spoke. He was a graduate student in Art History at Columbia when events steered him into research on defense contractors. I worked with him at NACLA. He is the author of Blood and Oil, a professor and defense correspondent for The Nation.

Klare detailed the lessons learned from Vietnam by the Defense Department: to use an all volunteer economic draft, to rely on technology, speed and fire-power, to attempt to reduce U.S. casualties and shorten the military engagement, to outsource military services and carefully control media coverage. He said that Defense Department brass have been extremely critical of the political bungling that has prolonged the military engagement. Many in the military see this as “dishonoring the commitment” of the servicemen and women.

The Friday morning panel also included Tom Engelhardt of the TomDispatch blog and Callie Maidhof, a Columbia student antiwar activist who spoke of the five days of antiwar action undertaken to commemorate the five years of the war. For thirteen hours each day, Columbia antiwar activists read the names of the dead – the known Iraqi dead and the U.S. dead. A gong was sounded for each death. On April 23rd, antiwar activists “hooded” Columbia’s iconic Alma Mater sculpture. With its face covered by black cloth, it appeared as an eerie reminder of Abu Ghraib torture victims.

The first Friday afternoon panel was on Feminist Legacies of 1968. It was a poignant reminder that 1968 preceded the women’s liberation movement. Women who were at Barnard and Columbia forty years ago were often the sandwich-makers, not the speakers. Although 250 women were arrested, their names are not well known. The full effect of the women’s movement can be seen, however, in the current generation of activists where women take leadership roles. The feminist panel included poets, professors, authors and activists. Ti-Grace Atkinson, Rosalyn Baxandall, Elizabeth Diggs, Christine Clark-Evans, Grace (Linda) LeClair, Sharon Olds, Catharine Stimpson participated. They recounted the early days of women’s liberation organizing – picketing the New York Times for gender-segregated want ads, participating in New York Red Stockings and WITCH and the founding of National Organization for Women (NOW).

One of the speakers, Grace (Linda) LeClair, a co-founder of the Calvert Social Investment Fund and Executive Director of NARAL in New Hampshire, was a Barnard student in 1966. She lived off-campus with her boyfriend. When a newspaper reported outed her, she was called before the Barnard president. LeClair was expelled and never graduated. Her boyfriend suffered no such fate, graduating from Columbia.

An afternoon panel on Political Action and Official Response included a judge, law professors and a criminal defense attorney who were veterans of the 1968 protest as well as Lee Bollinger, the President of Columbia. West Harlem organizers infuriated by Columbia’s current expansion plans interrupted Bollinger. A third afternoon panel addressed Race at Columbia, Then and Now, with writer Thulani Davis moderating. It included Manning Marable, a Columbia professor, and two student activists, one representing the Black Student Organization and the other Lucha. Johanna Ocana of Lucha became an activist when the Young Republicans invited a speaker from the Minuteman and students, many of immigrant parents, organized protests.

In the evening a lengthy multi-media event described what happened in April 1968. This was before the era of instant communication, the internet and cell phones with cameras. As pictures projected on huge screens, the occupation story was recounted by Nancy Biberman, Raymond Brown, Leon Denmark, Larry Frazier, Robert Friedman, Stuart Gedal, Juan Gonzalez, Michelle Patrick, Mark Rudd and others. An assistant to New York’s mayor at the time told his side of the story as well.

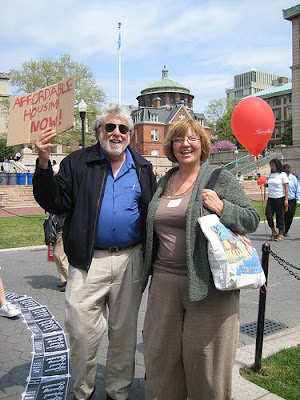

On Saturday, there were movies about 1968 shown and a panel on The Legacy of the Student Movement that included Todd Gittlin, now a Columbia University professor, and John McMillian, a Harvard lecturer. At noon, a Harlem contingent marched up Amsterdam Avenue protesting Columbia’s Manhattanville project. Joined by my daughter and brother-in-law we marched on to campus with them. Although the scheduled events continued, I went to only one more: Organizing, Activism, Engagement, Then and Now at which my daughter and I both spoke.

There was an odd disconnect between those passionate times and the scholarly panel discussions organized by alumni participants. Occasionally, the strident voices of Harlem residents who opposed a current Columbia expansion were reminiscent of that earlier time, particularly when they interrupted President Lee Bollinger. Contemporary Columbia antiwar activists and leaders of the Black Student Organization and Lucha, brought the present tense into discussion.

Many panels were dominated by male voices with credentials – professors and writers. When people lined up for questions, they frequently delivered polemics. It reminded me of being a young Texan in New York on a campus where the elite had been educated to believe they were the center of the known universe. There wasn’t much space for participatory democracy in the rarified Ivy League atmosphere forty years later. Not until the final panel that I attended – an event billed as an intergenerational dialogue – was there a structure that encouraged exchange. A table with microphones set in a circle allowed people to come and go (although some had to be encouraged to speak and then leave). There were more women’s voices and the familiar edge of now. Here, the younger generation showed what is easy to miss: the struggle continues.

The Rag Blog