Social Change in America : Learning from History

Creating a New Progressive Era

by Jack A. Smith / July 3, 2008

Jack A. Smith is editor of the Activist Newsletter and a former editor of the radical newsweekly The Guardian.How can poverty and grave economic inequality be significantly reduced in the United States? Under what conditions might it be possible to bring about a period of significant progressive reform that would address our country’s major social problems?

As the income and living standards of the poor, the working class and a significant sector of the middle class in America have declined, a quite small portion of the population known as the upper class has become wealthier and more powerful than ever. One would have to revisit the Gilded Age of the late 1800s or the Roaring Twenties just before the 1929 Great Depression to locate comparable contradictions between the rich and the rest of the American people.

There are many distressing statistics that demonstrate the extent of economic inequality in the United States. The following is a telling illustration:

The top 20% of wealthy families in the U.S. now possess 84.7% of all assets and wealth. The top 5% alone control 58.9%, and the richest 1% command 34.3%. The “bottom” 80% possess of 15.3% of the nation’s wealth. The bottom 40% within this total have accumulated 0.2%. That’s two-tenths of one percent owned by 120 million Americans, while 34.3% is possessed by 3 million.

According to progressive economist William K. Tabb, writing in Monthly Review (July-August 2006), the Bush Administration’s economic policies “carry echoes which have been heard down through our nation’s history and have taken on resonance analogous to the Gilded Age and the Roaring Twenties, other periods when conservative ideology and politics held sway and rapid increases in inequalities were produced by deregulation and variants of laissez faire policy and Social Darwinist thinking. But in all periods, we have had a government of the rich that has acted in the interests of the rich.”

Columnist and Princeton economist Paul Krugman, writing in the N.Y. Times on April 27, 2007, argued that “Income inequality… is now fully back to Gilded Age levels… Last year… a hedge fund manager took home $1.7 billion, more than 38,000 times the average income. Two other hedge fund managers also made more than $1 billion, and the top 25 combined made $14 billion… The hedge fund billionaires are simply extreme examples of a much bigger phenomenon: every available measure of income concentration shows that we’ve gone back to levels of inequality not seen since the 1920s.”

There is a clear cause and effect when the “upper” classes get richer and the “lower” classes get poorer. It often derives from the ability of those with power and wealth to manipulate government policy regarding taxes, regulations, and programs to further benefit themselves at the expense of those lacking power and wealth.

This is hardly unique in American history, but more prevalent at certain periods, such as the present moment when economic inequality and poverty are at high levels. We will focus upon three comparable periods in the past that generated a progressive response ultimately resulting in major social and economic reforms.

The United States advertises itself as the world’s outstanding example of democracy. But how can a democracy function properly and fully in conditions of gross economic disequilibrium, especially when class inequality is compounded by racial and gender inequities as well?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt recognized this contradiction when he declared in 1944 that “true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence.”

Economist Lester Thurow, in his 1999 book about the income gap titled Shifting Fortunes asked: “How does one put together a democracy based on the concept of equality while running an economy with ever greater degrees of economic inequality.”

American progressives of an earlier era understood this as well. Historian Richard C. Wade, writing about the reform struggle of the early 1900s, noted: “Progressives agreed that the central question of their times was how to control the power of concentrated wealth in a democracy.”

No wonder increasing comparisons are made between America in the early 2000s and the Gilded Age — a period of enormous wealth and opulence for the few and exploitation and oppression for the many.

An important difference between this earlier period and now is that in the late 1800s/early 1900s, there was a substantial fight back against the machinations of wealth and power, while in comparison today’s response has largely been confined to the wringing of hands.

Progressive movements arose in opposition in several past situations of extreme inequality and flaunted wealth. There were people’s organizations out in the streets; unions were marching; there were sizable left groups organizing and leading struggles. At times, popular pressure obliged the ruling parties to put some restraints on the corporations, investors, financiers, and their hangers-on, and even to pass legislation favorable to working people.

But now, after a quarter-century of stagnating wages, with a recession looming over the country as prices are rising and incomes are falling, as workers are losing their jobs and homes, Washington is spending trillions on aggressive wars and a relative pittance on new programs to help the masses of people.

There’s a class war going on, initiated and led by wealth and power. Various administrations in Washington in recent decades offer a perfect example of our government’s penchant for coddling the rich and ignoring the needs of working families. But aside from small left organizations and reform groups, some unions and a few politicians, what forces in our society are truly fighting for the poor, the working class and lower middle class majority of the American people? It is certainly not the two ruling parties.

There’s an election going and neither Democrat Barack Obama nor Republican John McCain has put forward a worthwhile immediate program to counter high prices for food and fuel, increasing unemployment, and depressed incomes. Neither offers a strategic program to greatly reduce poverty and inequality in America, to create good new jobs and affordable housing. Neither will contemplate big cuts in the military budget nor sharply increasing taxes for the rich to pay for these programs.

For over 200 years in America, virtually every decisively important government program or law that benefited the masses of people was the product of persistent, hard-fought struggle led by progressive and left social or political or labor movements, or all in combination. This was true at various points in history in the attainment of an eight-hour day, vacations, and a minimum wage; the right of women to vote and to work in jobs previously held by men only; the granting of Social Security pensions, Medicare and Medicaid; the end to lynch laws, the poll tax and formal racial segregation — and just about every other advance that has taken place in our society.

None of it was a gift. All of it was a struggle. And it’s the only way poverty and inequality — and all comparable abuses — can be reduced significantly.

The last period of relatively progressive governance in America lasted a few years and ended four decades ago when President Lyndon B. Johnson left office. LBJ is accurately remembered as the president who led the U.S. into the quagmire of the imperialist Vietnam War. But his extensive and fruitful “Great Society” domestic program was the final attempt to continue New Deal-type reforms initiated by President Roosevelt during the Great Depression when masses of people were demanding relief and reform.

The great obstacle to progressive social change in America today is that we have been living in conservative political times for decades. The nation is just emerging from eight years of George W. Bush’s hard core ribald neoconservatism and preemptive wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; preceded by eight years of Bill Clinton’s centrist compromise with the rightists, killer sanctions against Iraq and the unjust war in Yugoslavia; four years of George H. W. Bush’s conservatism and the first war against Iraq; and eight years of Ronald Reagan’s reactionary Cold War policies, subversion throughout Central America, and right wing economic programs.

The 2008 election offers the U.S. people a choice between centrism and neoconservatism — all in the name of an ambiguous mantra of undefined “change.” This means that the right and center — the political tendencies least willing and able to end gross economic inequality and banish poverty in the U.S. — will dictate national policy through the next four years as they have in the past.

It doesn’t have to be this way. There were periods in American history when conservative times did transform into progressive times. When this happened it was almost invariably a consequence of popular mass struggle for affirmative political reform.

Today, the U.S. left — from left-liberalism and progressivism to social democracy, socialism and communism — is weak and without meaningful influence. And our critically important union movement is weak as well, with a leadership that remains wedded to the “lesser evil” centrism of the Democratic Party in return for token political compensation.

When the American left revives, as it certainly will, and popular mass struggle resumes, the conditions will exist to bring about a new period of substantive social, economic, and political reform.

Lately there have been some reports of an incipient progressive upsurge within the Democratic Party that might seriously address matters of poverty and economic inequality, among others.

Undoubtedly there are many left-liberal and progressive Democrats who are justly disappointed by the cautious performance of their party’s majority in Congress and by the refusal of the leadership to venture even a trifle to the left of center. Groups such as Democrats.com and MoveOn.org, among others, are cited as evidence of a progressive resurgence and even a possible harbinger of an effort to seize party leadership “from the bottom up.”

Our country would benefit if the center/center-right Democratic Party moved to the center-left in the next few years on the basis of agitation within its ranks. But it is far-fetched to think it will do so after the party leadership’s diligent and successful efforts over the decades to bury liberalism and completely reject the hint of social democracy implicit in the first few years of FDR’s New Deal.

At some point there will be another period of progressive advance, such as several earlier times in America’s history. When that happens it probably will be generated from outside the Democratic Party and consist of mass movements with progressive and left leadership around such key issues as economic reform, peace, inequality, poverty, jobs, housing, militarism, imperialism, union rights, and so on.

Such circumstances might influence the Democrats to take some action. Or it could lead to another Progressive Party, as it has done thrice before on the national level (1912, 1924, and 1948) and four times on the state level, not to mention many other left third parties.

Let’s briefly look back to some earlier periods of progressive reform in our history. While there were active reform movements in the years before the Civil War (abolition and women’s rights), a broad major reform struggle began in the 1870s and lasted with varying levels of intensity about 40 years. It took place during two historic periods: the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era.

The name Gilded Age was taken from a 1873 book of that title penned by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner. Their use of “gilded” derived from Shakespeare’s King John: “To gild refined gold, to paint the lily… is wasteful and ridiculous excess.”

The Gilded Age officially began with the end of Reconstruction in 1877. It was weakened by the decimating depression of 1893-97 and declined at century’s end, though many of its conditions continued into the Progressive Era, which lasted between 1900 and World War I.

During the later 1800s America changed from a rural agrarian society into a mixture with urban industrial development that greatly accelerated the Industrial Revolution and created fabulous fortunes for the wealthy, and extreme exploitation for working class men, women and children. Long hours, low pay, and miserable living conditions painfully afflicted multimillions of American workers as unrestrained capitalism ran amuck.

Simultaneously, as the U.S. was adjusting to a post-Civil War, post-Reconstruction period of booms and busts (there were three depressions in the Gilded Age), the great majority of former slaves were forced into a new type of oppression under Jim Crow segregation laws (the model for pre-liberation South Africa’s apartheid system.) It took 90 years, the civil rights movement, and the 1960s reform period to end formal racial segregation, though racist inequality still exists in America.

The Gilded Age, according to author Steve Fraser in an article for TomDispatch.com April 28, was characterized by “crony capitalism, inequality, extravagance, Social Darwinian self-justification, blame-the-victim callousness, [and] free-market hypocrisy.”

In response, he wrote, “Irate farmers mobilized in cooperative alliances and in the Populist Party. Farmer-labor parties in states and cities from coast to coast challenged the dominion of the two-party system. Rolling waves of strikes, captained by warriors from the Knights of Labor, enveloped whole communities as new allegiances extended across previously unbridgeable barriers of craft, ethnicity, even race and gender.”

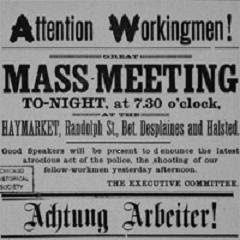

The strikes were militant and massive, and included the Great Railroad Strike of 1877; the 1886 railroad strike; the 1892 Homestead Strike; the Great Uprising of 1886 composed of nationwide strikes and demonstrations for an eight-hour work day, which led to the legal lynching of four anarchists on trumped up changes after the Haymarket Riots; and the 1894 Pullman Strike conducted by the American Railroad Union and led by socialist Eugene Debs.

The new labor movements were the only protection most American workers had against unbridled capitalist greed. The Knights of Labor, one of America’s first great unions, was formed in 1869 and played an important role in the working class fight back during the Gilded Age. It faded in the late 1880s. The more restrained American Federation of Labor was formed in 1889. The militant Western Federation of Miners was organized in 1893, and the revolutionary International Workers of the World, the Wobblies, came about in 1905.

The Populist (Peoples) Party was founded in 1890 to put forward demands ignored by the two ruling parties. It received over a million votes in the 1892 presidential elections on a platform calling for direct election of U.S. Senators, a secret ballot, referendums, recall of elected officials, direct primary balloting and opposition to the gold standard. A number of its candidates became governors and members of Congress.

By the next presidential election in 1896, the Democratic Party had adopted a number of the populist demands which it had earlier opposed. The Populist Party then supported Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan, who lost to Republican William McKinley. That was the beginning of the end for the populists. Their party quickly declined and dissolved in 1908.

The excesses of capitalism were mainly addressed by reforms during the Progressive Era, but some took place in the 1890s, such as the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890), which outlawed business monopolies; The Interstate Commerce Act (1887), which protected small shippers against powerful railroads; and the Civil Service Act (1883), aimed at ending corruption, which substituted the merit system for the spoils system in filling government jobs.

The Progressive Era was a period of great reform in response to the extreme exploitation of working families that accompanied swift industrialization and the growth of cities at a time when millions of poor immigrants were pouring into our country. The working people benefited from these reforms, but so did capitalism, of course, the regulation of which was essential to rationalize and strengthen the system, not replace it.

According to a superb college textbook on American history, Who Built America? (vol. 2): “Scholars [of the Progressive Era] have been unable to agree on exactly what Progressivism was. In fact, Progressivism encompassed many distinct, overlapping and sometimes contradictory movements: it was working people battling for better pay and control over their working lives; it was women campaigning for more equality and the right to vote at the same time as African Americans were being disfranchised in the South. It was corporations and their allies pushing to make city governments more businesslike; it was middle class reformers closing saloons and prohibiting the sale of alcohol; it was politicians and presidents extending the power of government to ‘bust trusts’ and regulate corporate activity.

“Sometimes these various reform forces worked together, sometimes they fought each other. Each responded in some way to the profound economic and social changes of the Gilded Age, but they differed in their interpretation of problems and solutions. As coalitions shifted, these diverse campaigns laid the foundation for modern American politics.”

The progressive movement had a number of concerns: the terrible conditions of working class life, from child labor to poor housing and ill health; the abuses of robber barons and business owners; the lack of government regulation of the marketplace; women’s suffrage; prohibition; race oppression; direct elections (to the Senate); electoral reform; and anti-monopoly reform.

There was another concern as well, according to the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers: “Fear of the expansion of socialism and Marxism provoked many in the upper class to support more moderate reform efforts as a means to ease the growing tensions between rich and poor and head off more extreme threats to their privileged role in society.”

President Theodore Roosevelt, who as vice president entered the White House in 1901 after President McKinley was assassinated, was the foremost reform politician during the Progressive Era. Although a man of wealth, an open imperialist, and staunch advocate of capitalism, he opposed the excesses of the Gilded Age as counter-productive to the interests of the United States and to his own vision of America as a burgeoning world power. TR, as he was known, believed that “the man of great wealth owes a peculiar obligation to the state because he derives special advantages from the mere existence of government.”

Republican Roosevelt left office in 1908 after presiding over the passage of a number of reforms demanded by the progressive movement and the expansion of federal authority. He was succeeded by his own vice president, William H. Taft. Out of office but still riding the progressive wave in 1910, TR outraged his own class be declaring: “I believe in a graduated income tax on big fortunes, and… a graduated inheritance tax on big fortunes.”

Convinced that Taft and the Republican Party had turned against progressivism, Roosevelt unsuccessfully sought to obtain the party’s nomination in the 1912 presidential election. He then bolted the Republican Party and, with support from the progressive movement, formed the Progressive Party (known also as the Bull Moose Party) with an extensive reform agenda, the purpose being “to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics.” With the GOP split, the Democratic Party’s Woodrow Wilson won the election. Roosevelt was second and Taft last. Union leader Debs, running at the candidate of the Socialist Party, came in fourth with 6% of the vote. The Progressive Party collapsed in 1916.

Among the federal reforms of the Progressive Era were the following:

The Newlands Reclamation Act (1902) a conservationist measure; the Elkins Act, the Pure Food and Drug Act (1906 and 1911), making sure that companies label ingredients; the Meat Inspection Act (thanks to writer Upton Sinclair’s exposé in his novel The Jungle); the Federal Reserve Act; the Clayton Antitrust Act, opposing monopolies and ruling that labor unions did not fall under antitrust laws; and the Federal Trade Act that established the Federal Trade Commission that is supposed to investigate “unfair business practices.”

In addition, laws were passed regulating the drug industry, establishing federal controls over the banking industry, and improving working conditions. Further, two progressive constitutional amendments — the power to tax income and the direct election of Senators were approved in 1913. Another progressive cause, women’s suffrage, was passed in 1919.

The Roaring Twenties were hardly progressive. It was a period of extreme Republican laissez faire economics, until the stock market crashed in 1929, plunging America and the world into the Great Depression.

There were radical moments in the 1920s, however, including the resurrection of the Progressive Party, which fielded Wisconsin progressive Republican Sen. Robert M. LaFollette Sr. as its 1924 presidential nominee against conservative candidates from both the Democratic and Republican Parties. LaFollette, whose program included nationalization of large industries including railroads, higher taxes for the rich and lower taxes for working people, and collective bargaining for workers, was supported by labor, socialists and liberals. With nearly five million votes — 16.6% — La Follette came in third. The Progressive Party dissolved in 1946, long after it ceased activity on the national level. During these years in its Wisconsin stronghold the party elected a governor and six members of the House of Representatives.

By the second half of the conservative 1920s the rich-poor gap was reaching Gilded Age proportions. Herbert Hoover, who defeated liberal Democrat Al Smith in the 1928 election, was the third Republican elected to the presidency during the decade. In accepting nomination, Hoover declared: “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land. We shall soon… be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation.”

Hoover assumed office in March 1929. The Great Depression began seven months later, catapulting most of the working class and middle class into exceptionally hard times. Consistent with his conservative ideology of waiting for the “market” to cure itself, Hoover did practically nothing as the economy crumbled in the three years until the 1932 election, which gave rise to the greatest period of progressive reform in U.S. history.

The Democrats nominated New York Gov. Franklin D. Roosevelt, a fifth cousin to Theodore Roosevelt. He declared in his acceptance speech, “I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people,” and his program became known as the New Deal. FDR, as he was universally known, captured 57.4% of the vote against 39.7 for Hoover, and remained in office to four terms. He delivered the famous line, “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” in his first inaugural address in 1933.

Roosevelt was under extreme pressure when he entered the White House. Unemployment reached its peak that year — 25.2% — meaning one in four workers was jobless and many others were working for reduced pay and waiting for their jobs to disappear. Millions of families were suffering great distress and relief from Washington barely existed.

From the day he entered the White House, Roosevelt understood that his principal task was to preserve capitalism in America at a time when private enterprise systems around the world were experiencing economic disasters. There were two threats. One was that the downward economic spiral in the U.S. might lead to a total collapse. The other was the fear that the working class might seek to replace capitalism with socialist or revolutionary communist alternatives. At the time, these were quite rational speculations.

The political left had been organizing since the day the stock market crashed. For instance, according to Who Built America?, just weeks after the market crash “the Communist Party organized the first of what was soon a nationwide network of ‘Unemployed Councils.’ These Communist-led neighborhood groups worked to aid the unemployed with immediate problems of rent and food, to apply pressure for improved relief programs, and finally to recruit new members to join the party. On March 6, 1930, the communists held a series of rallies on what it dubbed International Unemployment Day,’ demanding government action. In city after city, the turnout far exceeded expectations.”

The Communist Party was active throughout the 1930s, in all the major cities, in the unions, in the South among poor black sharecroppers, in Harlem stopping evictions and fighting for unemployed workers. Near the end of the 1930s CP membership rose to its highest number ever, 100,000. Many other progressive and left groups, including populist farmers, were organizing as well, but the communists were the most energetic.

Unions were active but did not come into their own until late 1935 with the formation of the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations). In little more than a year union membership in the U.S. rose from four million to seven million. Confrontations between labor and management sharply increased as companies resisted collective bargaining, often engaging in redbaiting in the process. Many in the wealthy class and their minions in corporate management viewed unionization as a red plot.

Company brutality, exercised through local police and private security thugs, increased as labor became stronger. Police shot and killed 10 striking workers outside a Chicago steel factory in May 1937. In the same month, a Ford company guard viciously beat leaders of the CIO’s United Automobile Workers union.

The less activist American Federation of Labor (AFL) was founded 46 years earlier as a craft union, organizing each craft — such as plumbers, sheet metal workers or carpenters — into separate unions. The CIO organized workers around entire industries — auto, steel, coal, and so on, conveying to each member a sense of mass and solidarity.

The CIO was known for its militancy and spectacular sit-down strikes. Many leftists including communists were CIO organizers and union militants at the time — often the most dedicated and hardest fighters for the union — even as a number of union leaders expressed anticommunist views in response to criticism from the owners. (The CIO purged most of its left militants in the late 1940s when it took a right turn in response to the Washington’s anticommunist campaign accompanying the start of the Cold War against the Soviet Union. It subsequently merged with the AFL and has generally supported some of the worst aspects of U.S. foreign policy ever since.)

The new president understood that the desperation afflicting American workers and their families, combined with the determination of the political, social, and union organizations demanding that Washington alleviate their plight, obligated him to proceed swiftly, decisively, and in tune with the progressive assumptions of the day.

Read the rest of this article here. / DissidentVoice

The Rag Blog