Don Swift : Paranoid Politics and the Legitimacy Crisis

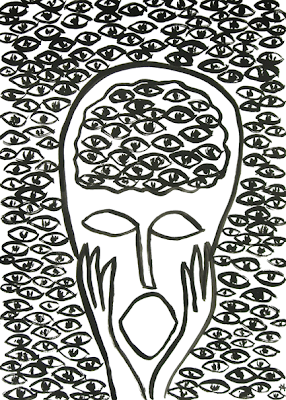

Paranoid politics:

How the legitimacy crisis helps the Republicans

The growing lack of confidence in government and democracy occurred most with white, blue-collar people. The extent to which this was directly connected to racial antipathy is difficult to sort out.By Don Swift / The Rag Blog / July 25, 2012

[See earlier articles in this series.]

The Paranoid Style

Throughout American history, there have been numerous highly emotional and somewhat irrational movements that were marked by paranoia, rage, and acceptance of conspiracy theories. They include the McCarthyites of the 1950s, the anti-Catholic “Know-Nothings” of the 1850s, the White Citizens Councils, the anti-Masonic and anti-Illuminati movements, and the populists of the 1890s. The angry farmers in the latter were not right-wingers.

The late Richard Hofstadter, an expert on status politics and the populists, lumped them together under the heading of the “paranoid style in American politics.” They all have in common the fear that they are about to lose or have lost something important, including social status.

He found that these people have a way of projecting their own undesirable traits onto the people they hate. Frequently, there is a hang-up with illicit sex. They are given to paranoid theories and fantasies, and there are “heroic strivings for evidence to prove… the unbelievable.”

Movements that exhibit the paranoid style generate a great deal of emotional energy and commitment among followers, and the Republicans have been the beneficiaries of this sort of zeal and commitment since Richard Milhouse Nixon unveiled his “Southern Strategy.”

To a degree, that strategy was anticipated by Barry Goldwater's 1961 Atlanta speech in which he said, “We're not going to get the Negro vote as a block in 1964 or 1968; [we ought] to go hunting where the ducks are.” Both strategies were designed to mine Southern racial antipathies for votes.

Populism -- with an emphasis on right-wing populism

Right-wing populism was an even more successful ploy for using hot button issues and cultural differences to recruit voters. Of course, this strategy sometimes overlapped with the Southern Strategy.

The New Right, which includes the Religious Right, is an example of right-wing populism, and it too clearly is an example of the paranoid style. It has added a great deal of heat to the political environment and could well have paved the way for more extreme manifestations of the paranoid style.

The Religious Right draws upon evangelical and conservative Protestants and traditionalist Roman Catholics, and the religious element has allowed them to claim for themselves a special legitimacy that their opponents supposedly lack. The religious dimension has also helped push the Republican Party toward fanaticism.

Retiring Democratic Congressman Gary Ackerman learned from a Republican friend that Republicans in their caucus pray, hold hands, and call upon God to work against measures proposed by their opponents. There is nothing wrong with praying, but it might be more helpful if they preyed for wisdom and open hearts.

Modern day right-wing populism appeals to people who feel dispossessed; they think some sinister elite looks down upon them and has betrayed them. Contemporary right-wing populism appeals to social groups who believe they are losing status and control of the national culture.

Hofstadter's basic definition of populism still holds, but today's scholars have rehabilitated the Populist Party of old, choosing to overlook their xenophobia, anti-Semitism, and weakness for conspiracy theories.

His probing of what he called the “reactionary” far right of Joseph McCarthy has been faulted because it could distort people's understanding of conservatism. His point was that the reactionary far right is not conservative by definition or tradition.

For him, the McCarthyites and John Birch Society were pseudo-conservatives. He noted that the McCarthyites called themselves “conservatives” and usually employed the rhetoric of conservatism. The problem was that they evinced “signs of a serious and restless dissatisfaction with American life, traditions, and institutions." He called them “pseudo-conservatives.”

Hofstadter, Daniel Bell, and Seymour Martin Lipset clearly indicated that McCarthy, who used some populist rhetoric, was something other than a populist, and this is also true of today'a Tea Party movement.

McCarthyism and the Tea Party are distorted manifestations of extreme nationalism. The identity crisis noted by Huntington helped fuel the movement. It points in the direction of a nationalistic movement rather than populism.

The second development that points to something other than populism is a growing legitimacy, wherein people question the value of our government. It too laid the groundwork for the Tea Party and is known for the kind of anti-government sentiment that marks the Tea Party.

Legitimacy crisis

Political scientist Stanley B. Greenberg relates today's strong anti-government sentiment to a legitimacy crisis in which more and more people question whether democratic government can work. Scholars have been tracking a legitimacy crisis for decades, and it has recently grown to very substantial proportions as only a quarter of citizens have a positive view of government.

The growing legitimacy crisis made it possible for political fundamentalism in the form of the Tea Party to become a great political force almost overnight. The legitimacy crisis reflects high levels of disenchantment and feelings of betrayal. The term “legitimacy crisis” strictly can mean that a major breaking point has arrived and or that many perceive that the future existence of a healthy state is threatened.

The crisis should be acute rather than chronic, and one would expect it to come in response to dramatic adverse changes. However, scholars have decided not to use the term in its strictest sense because a legitimacy crisis can be relative and exist for some people and not others. If people perceive that a legitimacy crisis exists, then it exists for them.

Pollsters like Daniel Yankovich have been tracking ebbing confidence in our institutions since the last half of the 1960s, and it has only recently gathered critical mass. Declining confidence led to dissatisfaction and alienation. President Jimmy Carter's pollster, Pat Caudell, thought the problem was so great that he persuaded the president to give an ill-advised television speech on the subject in 1979.

Carter was careful in the way he broached his topic, and he never used the word “malaise” but an effective opposition information strategy made that word the keep to the speech and Carter's tone was even switched from cheerleading and optimism to that of gloom and doom. The problem after that was unaddressed by public officials.

By 1980, there were many scholarly references to a legitimacy problem. President Ronald Reagan, whose job should have been to help our political system work, perhaps unwittingly contributed to greater skepticism about its value. Today, some of these anti-government themes are standard Republican talking points, and some people who were once in the extremist fringe groups are now recognized Republican leaders.

Reagan taught people to believe that government helped folks conservatives thought irresponsible, not hard-working dutiful people like themselves. In 2011, only 25% of the American people expressed confidence in the future of the American system of government.

Anti-government rhetoric

Much of the anti-government rhetoric now spouted by the Tea Party members can be traced to the various fringe movements of the recent past -- the militias, the Constitutionalists, the Alaska Independence Party, the Christian Identity movement, the West Virginia Mountaineer Militia, and others.

All these communities of resistance and defiance of change have authoritarian and nativist characteristics. The two go hand in hand. Above all, they react against change. They see the government as an agent of unwanted change and they set out to disrupt and replace it.

They are serious about destroying government as it is and are attracted by the anti-government tactics of Republican politicians who claim to hate government but really want to control it.

Retired Republican Congressional aide Mike Lofgren wrote that several years ago a superior explained to him that it was Republican strategy to obstruct and disrupt government. By damaging the reputation of government, the Republican Party will benefit at the polls because it is programmatically against government.

A few months ago, he was told that the party would create an artificial debt limit crisis for the same reason, to win votes by making government look bad.

Though academicians and pollsters have been tracking declining confidence in our system for a long time, it was only in 1974 that ABC began asking about confidence in the future of democracy and liberalism. People identified the Democrats and liberalism with government, so distrust of government hurt the Democrats and made it easier for Republicans to make liberalism a dirty word.

Most Democrats had little idea that any of this was going on, and they suffered electoral disasters in 1972 and 1984 in part because many voters thought they were more concerned about helping those not working than those who were.

Compared to today, the situation in 1980 now does not appear very serious and the scholars who addressed it look like alarmists. British and European social scientists seem to think legitimacy problems grow out of the conditions of late capitalism that produce status stress and challenging economic conditions for middle class people.

That explanation is a bit difficult to apply to the United States where most people are impatient with talk about growing economic inequality. Some tie the growing lack of confidence to increasing social and cultural fragmentation. There is less cohesiveness, which in the past generated civility and sympathy across various cultural and social boundaries.

An essential characteristic of this growing sentiment was the idea that our political system was becoming increasingly illegitimate because it did not respond to what voters wanted. It appeared that government had become a powerful entity that was somehow removed from the voters who were supposed to control it.

Blaming the Democrats

This building sentiment doubtless helped pave the way for the Tea Party movement. The Greenberg study found that people who doubted the legitimacy of government associated the Democrats with big government and blamed the Democrats for the nation's problems. A majority of people interviewed, who reflected a deep legitimacy crisis, agreed with Democratic positions on the issues but believed the party simply could not deliver on its promises.

They saw the venality of many progressive leaders, who valued contributions, perks, and reelection over serving the middle class. They came to think that representative government no longer worked and they gave up on the Democrats.

After the bailout of Wall Street, many of them moved to the right and into the Tea Party. This is probably when a full-blown legitimacy crisis arrived, because so many people had suspected for so long that government was some sort of evil, alien force.

Dismay with Wall Street over the financial collapse was brief. A retired University of North Carolina history professor accompanied Tea Party people on a bus trip to the Capitol and had a chance to explore their thought. He found that Tea Party folks blamed everything wrong, including the financial crisis, on government. They saw Washington in the same way many viewed Moscow in the Cold War era. Perhaps the Cold War conditioned many to see all problems coming from a single evil source.

Somehow, they had been persuaded not to blame the bankers. It was government regulations. Distrust of government had been growing for so long among these people that they readily accepted the view that government caused the financial crash.8

Greenberg did not think they would take a favorable view of the Democrats until that party moved to get big money out of politics and prove they put the middle class over Wall Street and big business. So long as national politics remains dysfunctional and the economy is weak, these people will not back Democrats, and their distrust of government will continue to help the Republicans.

They see Democrats as wanting to grow a government that does not work. These people are weary and impatient and not likely to see through the Republican tactic of using across the board obstructionism to prevent passage of economic stimulus legislation. They are still likely to blame the Democrats for not rescuing the economy overnight.

Blaming the poor

Focus group research shows that many of the most disaffected citizens lump together the poor, Wall Street, and big business among the irresponsible elements that Ronald Reagan warned about.

As these people on the Right focused more on what they thought was wrong, they exaggerated how dire the situation was. They equated programs to assist the poor with government's illegitimacy. When William Jefferson Clinton became president, a legitimacy crisis occurred for them in an ideological and cultural sense, and they set out to remove Clinton from office.

It is not difficult to see how the crisis mentality mounted for people on the Right. What was occurring was that the Republican Party was becoming the home for people deeply affected by the legitimacy crisis and also for people on the Religious Right who were disturbed that they had lost control of American culture.

In time, beginning in the Reagan years, many came to see the Republican party as their primary identity group. Increasingly they would come to assess what was fact and “true” according to this primary identity and what the admired leaders of their political identity group said and thought. It was quite different from the 19th century, when ethnic and religious identities usually came first.

An interesting phenomenon appeared among gay Republicans who were members of the Abraham Lincoln Society. With time, the party became more and more anti-gay and homophobic, but the Abraham Lincoln people continued to be active Republicans, placing their primary identity over that of being gay.

Thinking about poverty seems to have shifted over 50 years and has contributed to the mounting legitimacy crisis. When Michael Harrington published The Other America: Poverty in the United States, many shared his desire to deal with the problem. He wrote about a “culture of poverty,” which was the product of poverty and included emphasis on short-term gratification, low expectations, and a variety of social pathologies.

Lyndon Johnson made headway in addressing the problem, but too many Americans bought Charles Murray's claim that Johnson's War on Poverty had been a failure. Even worse, Murray successfully sold the idea that the poor are trapped by an unhealthy culture, which then produces poverty. Murray said welfare programs only make things worse, abetting more dependency.

In other words, Murray managed to turn Harrington's careful findings upside down. As a result, many saw the poor as responsible for their own problems. Murray's research was not all that strong or convincing but people were increasingly receptive to it in a harsher America where people were less inclined to respond positively to their better instincts.

Republicans and victimhood

For people who increasingly saw government as illegitimate, Barack Obama's Affordable Health Care Act set off two major alarms. They saw government getting larger and more powerful, and they saw billions being spent to help poor people and the likelihood that taxes would eventually be increased to cover the costs. People who distrusted government and doubted its legitimacy simply went into orbit.

Republicans came to see themselves as the honest taxpayers who were victims of a State that did too much for the poor. By 2012, this concept of victimhood was expanded to seeing taxpayers as victims of greedy public employee unions.

Beginning in 2010, some states like Minnesota and Wisconsin stripped public employees of the right of collective bargaining. Other states followed, and some states slashed pension benefits for new public employees. This was followed by the beginning of efforts to slash pensions of public employees who were already retired.

Increasingly Republicans, who had long defended the contract clause rights of corporations, were saying that retired public employees had no contractual rights because their pensions seemed overly-generous.

The growing lack of confidence in government and democracy occurred most with white, blue-collar people. The extent to which this was directly connected to racial antipathy is difficult to sort out.

When Barack Obama led the Democratic ticket in 2008, it lost among white working class voters by 18 points. Two years later, when the Great Recession had not yet abated, the Democrats lost among these people by 30%.

The Gallup organization found that the number of Americans who called themselves conservative grew from 37% in 2007 to 41% in 2011, suggesting that the Great Recession has helped theRepublicans.12

Ours is not a direct democracy; it is a representative democracy. Most voters pay little attention to the details of politics. When things are not going well, the "throw the bums out" mechanism kicks in. This mechanism can be gamed and can be used in combination with a legitimacy crisis.

Newt Gingrich took a decade to end Democratic rule in the House by creating havoc in the chamber and convincing voters that the institution had lost legitimacy, and in 1994 the voters pitched the bums out. After the death of Ted Kennedy, Barack Obama lost the ability to pass recovery measures in the Congress. Republicans stonewalled him and slowed recovery.

Frustrated that he had not worked an economic miracle, the voters punished the Democrats in 2010, and the voters gave the Republicans a huge victory in the House and six more seats in the Senate. The same strategy is at work in 2012, and the Republicans are banking on the voters not being very attentive to detail.

Romney, like Tom Dewey in 1948, is being vague and misleading. Things were very unsettled in 1948, and people blamed Truman. This time, we have lingering unemployment, due largely to Republican policies and obstruction.

Truman in 1948, had a badly divided party and was not well-funded, but he managed to educate the voters and carry the battle to the GOP. In 2012, the question is whether the voters are as educable as those in 1948. Can Obama catch Truman's fire and persuasiveness?

[Don Swift, a retired history professor, also writes under the name Sherman DeBrosse. Read more articles by Don Swift on The Rag Blog.]

The Rag Blog